Because judo is such a niche sport, it is actually quite common for individual judokas to seek out better training opportunities, often in distant lands, on their own. The late great Anton Geesink, the first non-Japanese to win a gold at the World Championships and the Olympics, had travelled to Japan alone to train because he couldn’t get enough quality training in the Netherlands. Mike Swain, an American World Champion, also went to Japan alone and trained there for a few years. One of my coaches, Franz Fischer, was another one who went to Japan alone, in his youth, so he could improve his judo.

In competition, you occasionally see players who are there alone. Sometimes it is because their country is not strong in judo and they are the only ones representing their country. Other times it could be due to circumstances. For example, in 1980 the Moscow Olympics faced a boycott led by the USA. Italy, in solidarity with the USA, forbade athletes from the army from participating (in Italy, all national judo players are employed by the army). Ezio Gamba quit the army (he was the only one in the Italian team to do so), travelled to Moscow alone, and won the gold medal by defeating Britain's Neil Adams.

Of course, it’s always better to go with a team. And if you have that opportunity, great. But what if you don’t have a team or even a training partner to go with you for overseas training or competitions? You can stay at home or you can go alone.

Throughout my competition career I did everything alone. Not by choice but because I simply didn’t have anyone to accompany me on my judo journey. When I decided to go to LA in the summer of ‘91 to learn competition judo, I travelled there with my German roommate but he wasn’t a judo player, so he did his own thing. We didn’t actually see each other that summer and only got together when it was time to head back to Austin to resume our studies.

To someone who wasn’t there and wasn’t going through what I did, those three months might seem like a very lonely time. But I was training full-time and was tired all the time so I really didn’t have much chance to feel lonely. When I wasn’t training, I was resting. Also, I was learning all these new things. Time went by quite fast.

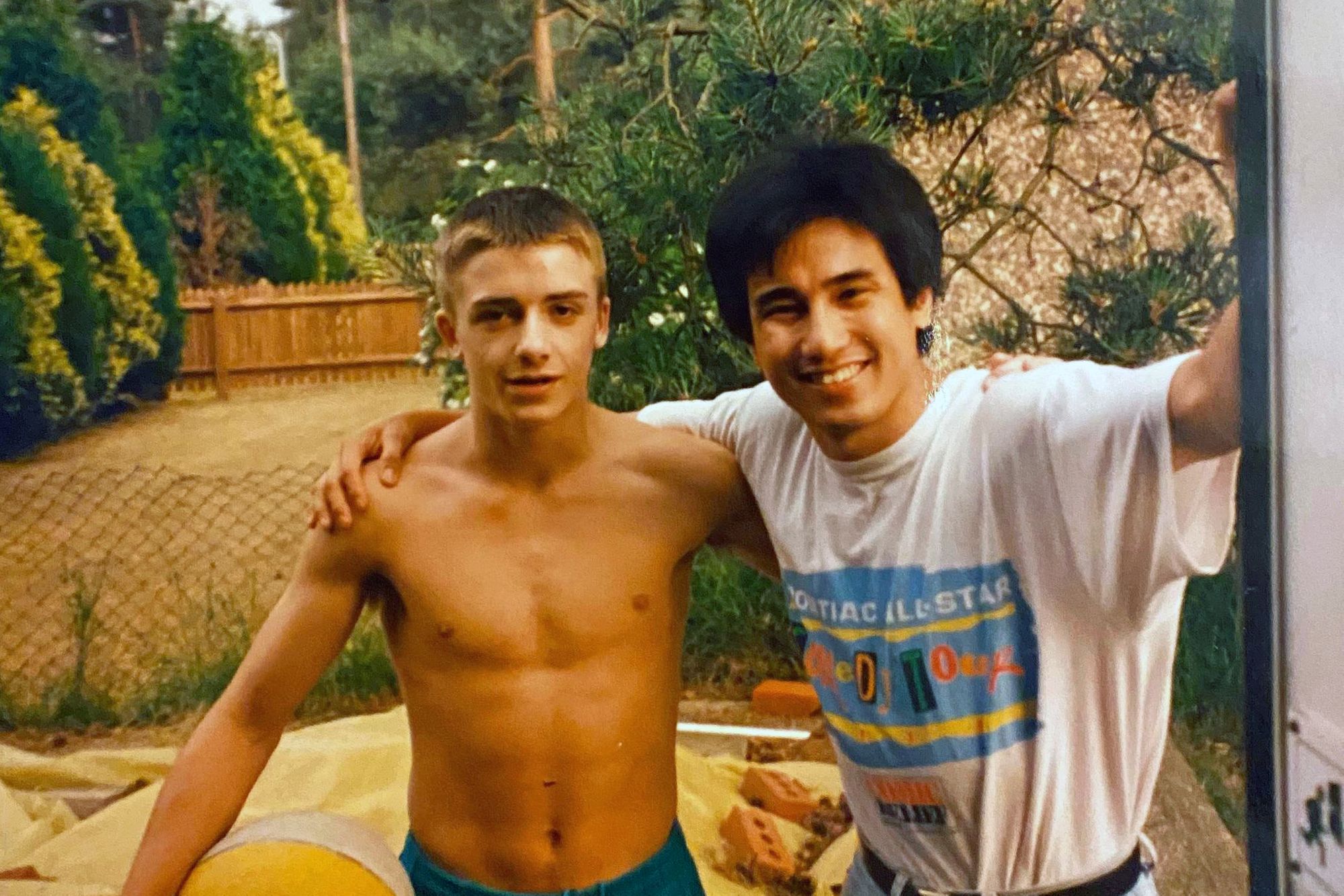

When I decided to go to Europe in the summer of ’92 to further my competition training, I travelled there alone. I still remember lugging my suitcases by myself from one place to another before I settled into Camberley. I was the only non-British player staying in Camberley at the time. I was an outsider but the boys there made me feel welcome. There were two other -60kg players staying there whom I trained with regularly. One was Julian Davies, who would eventually get a European silver medal; and the other was John Buchanan, who would later get a World bronze medal. When the British squad attended an international training camp in Birmingham (where the top Germans, Japanese and Russians were in attendance), they brought me along and I got to train with some of the best players in the world.

When I visited Germany to train at Russelsheim, again I was alone but my coach there had introduced me to Hans-Jorg (Oppy) who would become my judo buddy through the years. We spent a lot of time talking about judo and when I told him that I intended to compete in the 1993 World Championships without a coach, he told me he would pay his own way there and be my coach for my matches.

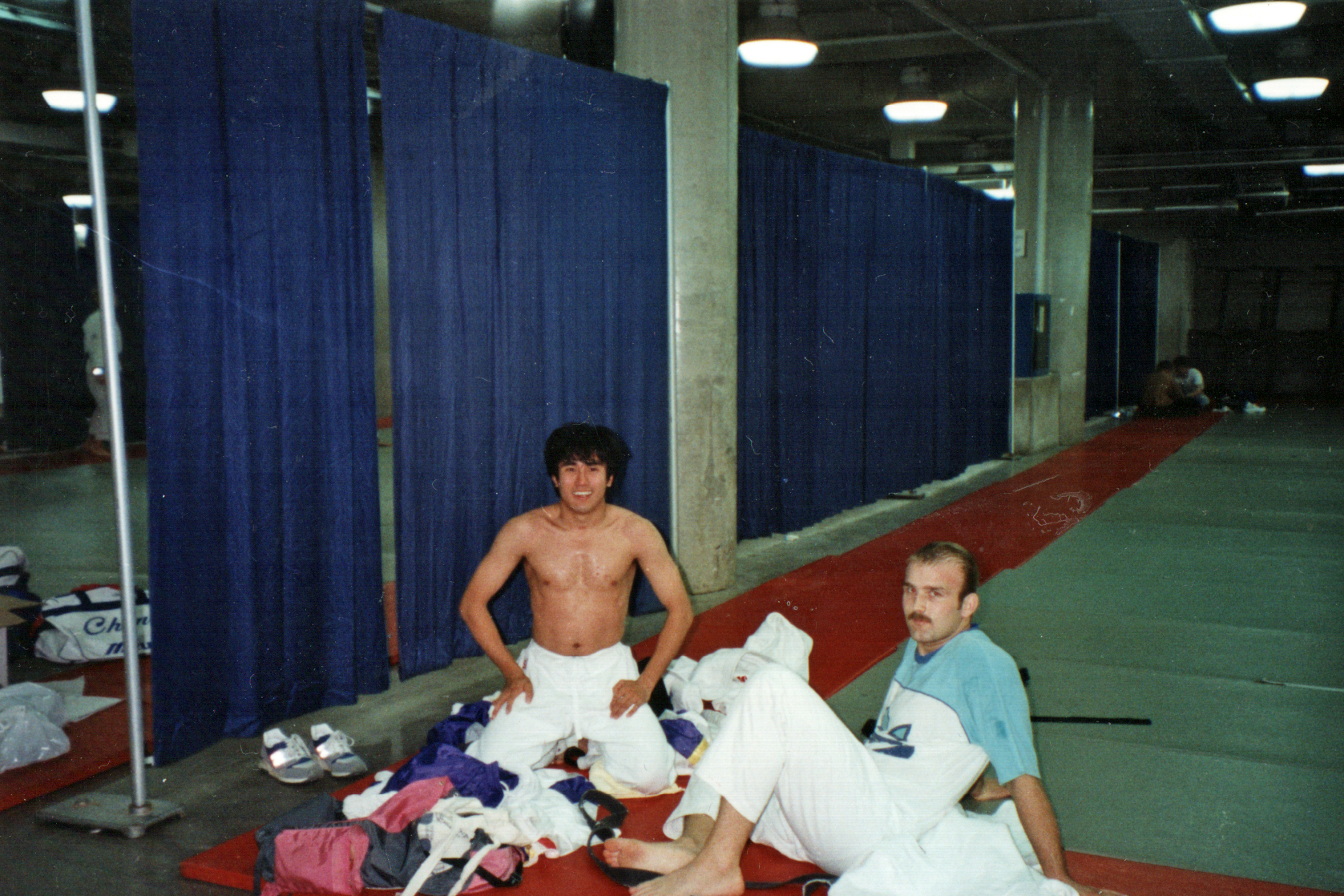

The next year, when the time came, Oppy kept his word and we met up in Hamilton, Canada. The honorary secretary of the Malaysian Judo Federation, Toh Kek Keong, had generously paid for our hotel there. I had not met Mr Toh in person before but we had communicated by letters (yes, snail mail) and he was impressed with my commitment to training so he decided to sponsor some aspects of my trip to the World’s.

I was the only Malaysian competing there. During the opening ceremony, I carried the Malaysian flag and probably was the only player in the stadium who had no teammates. I was alone, but not really alone because Oppy was there as my mat-side coach and Mr Toh was there to give me moral support.

Encouragement even came from an unexpected quarter. When I was stepping onto the tatami for my first match, an Indonesian referee walking past me said: “Fight hard, remember you are not only representing Malaysia but Southeast Asia as well”. I remember feeling, “I really have to win this one”. Fortunately, I did. Mr Toh was delighted. Oppy was ecstatic. I'm sure the Indonesian referee was happy too.

When I was working for Ippon Books in London, I often had to make trips to other European countries to expand the distribution of those books. That entailed meeting judo personalities in those countries and getting them to carry our books. I made those trips alone but again I was never truly alone. Your judogi is like a passport. I was always welcomed at judo clubs wherever I went.

In 1996, after I had retired from competition, when the Atlanta Committee for the Olympic Games invited me to be the press information officer for judo, I travelled to Atlanta alone. David Finch, the famous photographer was there too but he was busy shooting pictures, so we actually didn't spend a whole lot of time together.

The person I ended spending a lot of time with was a journalist from the local newspaper, the Atlanta Journal-Constitution. He was a sports journalist assigned to cover the judo event and we got on really well. I explained the nuances of judo to him and he told me a lot about journalism and freelance writing work, which would later be very useful to me. He told me that to be a good freelance writer, you need to be flexible and adaptable in your writing style. As an example, he told me about the time he was hired to ghost-write a speech for a basketball player. “Here I was, this middle-aged Jewish guy writing a speech about what it meant to be a successful, young, black athlete,” he said.

I asked him how he did it. “You just do it,” he said. Strangely, that was good advice. In subsequent years, I have ghost-written things for a supermodel (for her book), countless CEOs (male and female, of all races) and once even for a prime minister (a speech for the opening of a shopping mall). Each time, I just did it.

Although the bulk of my early judo journey was experienced alone, they produced many good memories that have enriched my life. Had I been inhibited by the fact that I would have to go to some foreign training centre alone or go to some competition alone, I would not have experienced any of those things. Fortunately, I was less concerned about being lonely and more interested in furthering my experiences in judo.