If you've been in judo for some time, you will notice there are some players who are technically proficient and extremely confident on the dojo mat but all of that goes out the window the moment they step onto the competition mat. These types of players do really well in randori, throwing everyone in the dojo. But when they have to compete for real, they lose their nerves.

There are also players who generally do well in competition but get spooked when facing certain opponents, usually because of the reputation of that opponent. When I interviewed British Olympic bronze medalist Sally Conway, she talked about how in the European Championships, she had already lost to three-time World Champion Gevrise Emane even before they fought because she was so afraid of her.

Only when Conway was able to overcome her fear of Emane was she able to defeat her in the Olympics. The fear factor is very real and it's an impediment to competition success.

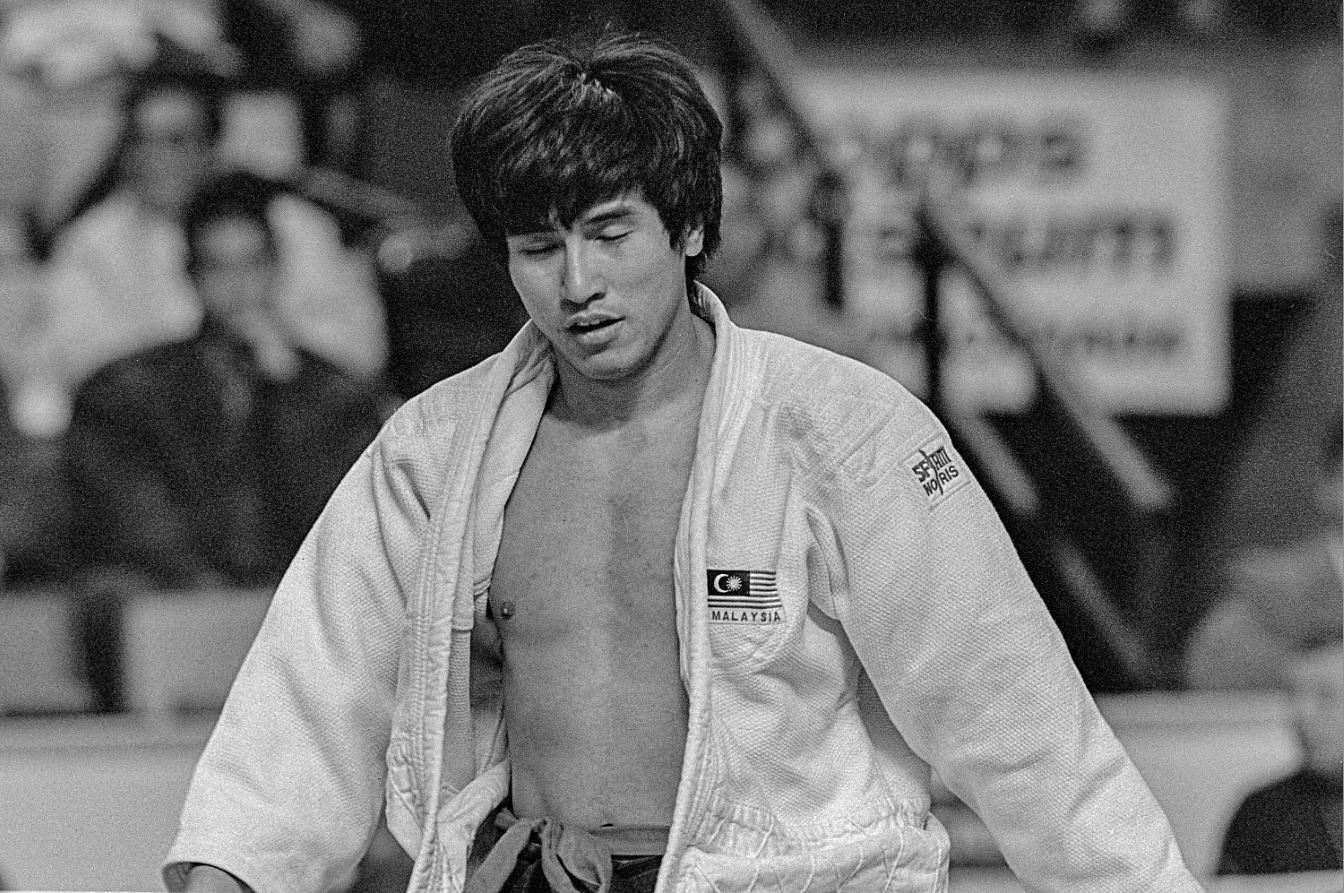

When I took part in the 1993 World Championships, my first match was against a player from Gabon who looked to be at least one weight class heavier. He was big and muscular and that made me a bit worried but not overly so. I figured he must have had to cut a lot of weight to make the -60kg division. He can't be that strong if he was dieting so much, I told myself.

I went into the match with confidence. He threw me with a leg technique that scored yuko (a smaller score than waza-ari, which existed in those days). I nearly caught him on the ground with a strangle but he managed to survive that one.

Time was running out but I stayed cool because he didn't feel as strong as he looked. I eventually caught him with a sleeve seoi-nage that I had seen the Polish Olympic and double World Champion Pawel Nastula do in the 1991 World Championships. Holding onto just one sleeve, he feigned a sode-tsurikomi-goshi to the right and quickly spun the other way to throw his opponent with a drop seoi-nage to the left. It was a brilliant move. I tried it and it work like a charm. Over my opponent went for ippon.

After the match, my matside coach (who was actually my judo buddy Hans-Joerg Opp from Germany), told me that the Gabonese player had trained in France in preparation for the World Championships. "I didn't want to mention this to you before the match because I knew it might affect you negatively," he said.

He was right. My friend understood the fear factor. If I had known my opponent had trained in France, I would have entered the match quite fearful of him. But because I had no idea, I was able to fight him without the impediment of fear, which allowed me to do my technique.

I ended up getting 13th place in the 1993 World Championships, which was not as good as I had hoped but it was a better placing than any Malaysian had ever achieved (this still holds true until today, actually).

The Malaysian Judo Federation was ecstatic and the following year, they invited me to return for the 1994 National Championships. They even paid for my plane ticket from the USA, where I was studying.

When I arrived for the competition, I was surprised to see that not only had my name been entered into the -60kg division, I was also entered into the Open Weight division. That meant not only did I have to fight heavyweights, I would also have to alternate between fighting my weight division on one mat and quickly going over to the other mat to fight the Open weight division, which was being run concurrent to the individual weight class competition.

The day before the competition, all the players were at the venue to do a bit of judo workout. The -86kg champion (in later years this weight class would be adjusted to -90kg) came up to me and said, "13th place in the world! Let's see how good your grips are."

He took hold of my judogi and proceeded to whirl me around the mat. I indulged him and we did some grip-fighting. I'm not sure if he was trying to intimidate me or just being friendly in his own strange kind of way. Maybe it was a mix of both.

I got through the preliminary rounds of the -60kg division quite easily but very nearly lost the final. My opponent was from Sabah (back then Sabah had one of the strongest teams in Malaysian judo). Very early on in the match, he came in for a quick throw that landed me on my side. Yuko was scored. He immediately clamped on a hold-down and "osaekomi" was called. I'm not sure how I managed to escape but after about 10 seconds "toketa" was called. I had conceded only a koka (a smaller score than yuko).

Today, there's only waza-ari and ippon but back then the scoring system was more complicated. The lowest score was koka, followed by yuko, then waza-ari and finally ippon. No amount of kokas can beat a yuko. So you could have 10 kokas but one yuko would be superior. Similarly, no amount of yukos can beat a waza-ari. And two waza-aris of course equal to ippon.

So, at the start of the match, my Sabahan opponent had already gotten a yuko and a koka on the board. I told myself, "Don't worry, it's still early in the game. I can throw him for at least a waza-ari".

The only problem is I couldn't. After getting those two small scores, he became a different player. He was no longer attacking but defending and back-pedaling. I wasn't able to penetrate his defenses but the fear factor worked in my favor.

He was doing everything he could to fend off my attacks and at one point, he was so afraid he actually grabbed hold of my fingers to prevent me from doing anything. That's illegal. The referee saw this and gave him a chui penalty.

Back then, the penalty system was also more complicated than it is now. Today there are only shidos and with three shidos, you get disqualified. Back then there were four penalties: shido, chui, keikoku and hansoku-make. If your opponent gets a shido, you get a koka. If they get a chui, you get a yuko and if they get a keikoku, you get a waza-ari.

My opponent had received a chui, which meant I got a yuko in return. He was still ahead though because of the yuko and koka he had scored earlier. With less than a minute left in the match, I had to make a choice. Either try to get another yuko so that my scores would be superior or make him incur another penalty, which would be keikoku (and waza-ari for me). I decided to go for the penalty.

So I piled on the pressure while he continued to play the defensive game. With just a few seconds left in the match, the referee called "matte" and gave him a keikoku. And with that, I was able to win the -60kg gold medal.

The Open Weight fights were a lot harder because I had to go up against some heavyweight champions on my way to the final. For my quarterfinal match, I was up against the heaviest guy in the tournament, who weighed about 110kg. He was a previous Open Weight champion but by then was already way past his prime. Still, he was almost twice my weight.

I decided to play the penalty game. I figured it was easier to make him get four penalties than to throw him. The fear factor worked again for me. He was clearly much stronger than I was but he was a bit intimidated by my reputation. From the start, he back-pedaled. I pushed him to the danger zone and kept him there for 5 seconds, causing him to get a shido.

Back then, there was a one-metre perimeter around the main contest area called the "danger zone" where you are not allowed to stay inside for more than a few seconds. If you were in the danger zone, you had to get out. My opponent was twice my weight and a former champion. If he wanted to push back, I'm sure he could have gotten out of the danger zone but he was too fearful to push perhaps because he thought I'd drop under him for a seoi-nage or something like that. So, he stayed put and paid the price.

Three more penalties to go, I told myself. But I was confident because I could tell he was afraid of me. I decided to make him passive so I put in a flurry of attacks. These weren't real attacks but they looked real enough that it convinced him to go on the defensive. Matte was called and he was given a chui.

I took hold of his gi and started to move him across the mat. He was too concerned about a possible attack that he didn't realize he was stepping outside. Matte was called and keikoku was given.

One more penalty to go. I just grip-fought him like crazy, tugging and pulling at his judogi, making him move around in circles and basically looking passive. The referee called "matte" and gave him a hansoku-make (which meant ippon for me).

I had just beaten a player I had no business beating, and by ippon. All because of the fear factor.

That brought me into the semifinal where I had to face the -86kg guy who tried to intimidate me with his gripping the previous day. He had just won his weight class so he was the reigning -86kg champion, a title he had held for many years. He also happened to be the defending Open Weight champion and a Southeast Asian Games silver medalist at -86kg.

The odds were clearly in his favor. He had size, strength and experience going for him. But I had the confident arrogance of youth.

After we bowed and came to grips, I knew straight away I could win because his gripping didn't feel the same as the previous day. He wasn't as aggressive and seemed reluctant to attack.

My main technique was ippon-seoinage but I knew if I tried a standing seoi it wouldn't work because he was so much heavier than I was. A drop seoi-nage might work but if it failed he could choke me with koshi-jime. So, instead, I went for the sleeve seoi-nage that worked for me at the World Championships the previous year.

I took a single grip on his left sleeve, feigned a right sode and immediately spun left into a drop seoi-nage. He spun over onto his back. The crowd roared and I thought I had scored ippon. But alas it was only a waza-ari. I still had to fight on.

With only about a minute left in the match, I thought he would come at me like a bat out of hell but to my great surprise, he was still wavering and reluctant to attack. Time ran out on him and he lost his chance to defend his Open Weight title.

In the Open Weight final, I fought the -78kg champion (a weight class that would in later years be increased to -81kg), He happened to be the brother of the -60kg Sabah player I had beaten earlier.

Unlike the 110kg guy and the -86kg guy, this -78kg guy wasn't afraid of me. He attacked me relentlessly and managed to score a yuko. I gave it as good as I got and managed to get a yuko too. At the end of five minutes (back then a regular match was five minutes long), our scores were even.

Today, this would have meant Golden Score where the fight would continue until someone got another score. But back then, evenly-scored matches were decided by hantei (referees' decision). Basically the centre referee and two corner judges would decide who was the superior fighter.

All three of them gave the match to my opponent. So, he got the gold and I, the silver. It was a fair call because he was the aggressor in that match. The full five minutes was just a series of non-stop attacks. Not once did he back-pedal or go on the defensive. Even when he was ahead by yuko, he wasn't content to defend his lead. He kept coming at me trying to finish the match with an ippon.

The fear factor was missing and in the absence of that, there was no way a -60kg champion was going to beat a -78kg champion.

That experience taught me a valuable lesson. In judo, the mental game is very important. You could be a strong and technically-accomplished player but if you are fearful of your opponent, you might lose because that fear paralyzes you and prevents you from attacking them properly. You end up fighting defensively, which is no way to fight a match (and certainly no way to win one either).