One of our new members asked me to share a bit about my personal journey in judo. Let me do this in the form of a blog posting.

When I was a young boy I was fascinated with Bruce Lee, who did a form of kung-fu. I also recall buying an illustrated book on karate. I guess I thought martial arts was cool. But I never did enrol in any martial arts classes and I don't even think I knew what judo was at the time.

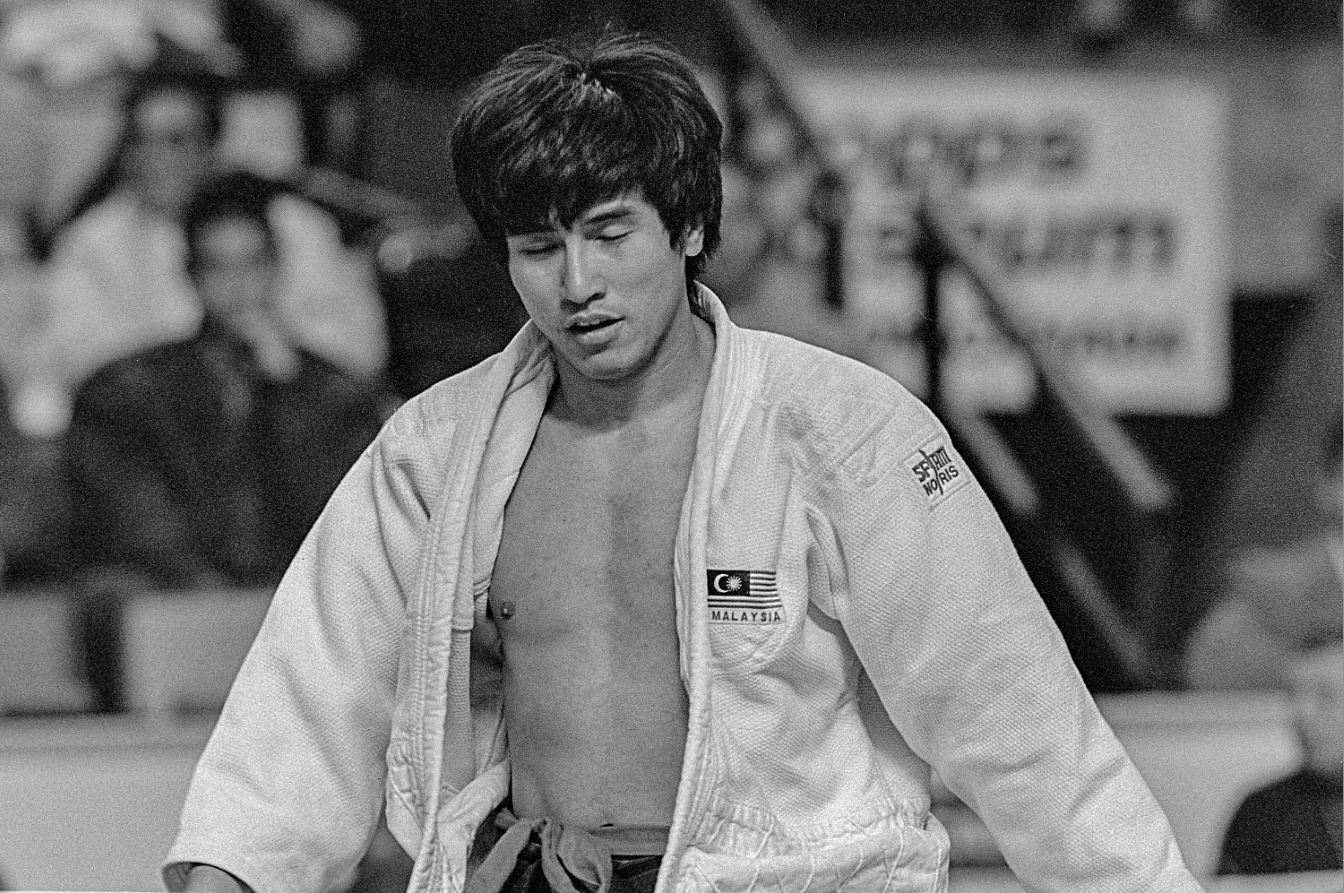

As a small boy, I grew up in the USA, so I played baseball and (American) football. Later when we returned to Malaysia, my dad introduced my brother and me to badminton and we played that a lot in high school. When I got a scholarship to study in Singapore, I tried out for the school badminton team but was not good enough. A few of my friends in the rugby team asked me to join rugby, which I had played for fun. They thought I was good enough to make it to the school team. But I was too small for rugby and opted instead for softball. I made it to the school team and the year I made it into the team, we won the National Schools Championship. So that was my first national-level gold medal in any sport.

I went to college at the University of Texas in Austin. Like any good Malaysian, I joined the university's badminton club and was so active in it, I eventually got elected president of the club. Right next door to the badminton hall was the judo club. And it so happened that the badminton sessions were held at the same time as the judo classes. So, I would often bump into judo players in the hallway as we lined up to get water from the water cooler.

I would often ask them questions about judo because I was curious about what they were doing. One day, one of them said, "Why don't you come over and give it a try?" So, I did.

My first experience in judo was really a shock to the system. There was a black belt named Brendan who was an ashiwaza specialist, and he footsweep me all over the mat. He didn't use any big throws, just foot-sweeps. And I couldn’t stop him. Once I got up, he'd footsweep me again. And again. And again. I couldn't believe it.

There was another black belt named Dominique, from France, who was a morote-seoi-nage specialist. He launched me into the air with standing morote-seoi-nage. Like Brendan, he was able to do this at will, over and over again. He was skilled at controlling me and made sure that I landed safely on my back even though it was my very first session, and I had not learned breakfalls yet.

I took to the sport immediately. Brendan and Dominique were not superheroes. They were not magicians. If mere mortals like them could throw me around like that, I wanted to learn that skill too!

The more I trained in judo, the more I fell in love with it. I wasn't able to throw anyone for a long time but that didn't frustrate me, it made me fascinated with judo. In due time, I realized I couldn't do both judo and badminton, so I gave up badminton. This was a game I had played since I was young but the decision to give it up was not difficult. I wanted to improve in judo and to do that I needed to focus.

After a year of dedicated training at the university judo club, I was awarded a brown belt by the club sensei. But I realized in order to become a better player, I needed to seek out the best coach in the country. I had heard of a famous judoka named Hayward Nishioka, who was a former USA national champion in the 1960s. He was a celebrity among martial artists and apparently he even knew Bruce Lee. Brendan, the ashiwaza specialist, lent me a book on ashiwaza written by Nishioka. I felt I had to seek him out. This was the era before the Internet or e-mail or anything like that. So, it was not so easy to find people. I knew he was out West in Los Angeles but did not have a phone number or address. I didn't even know which club he was attached to. I just knew he was in LA.

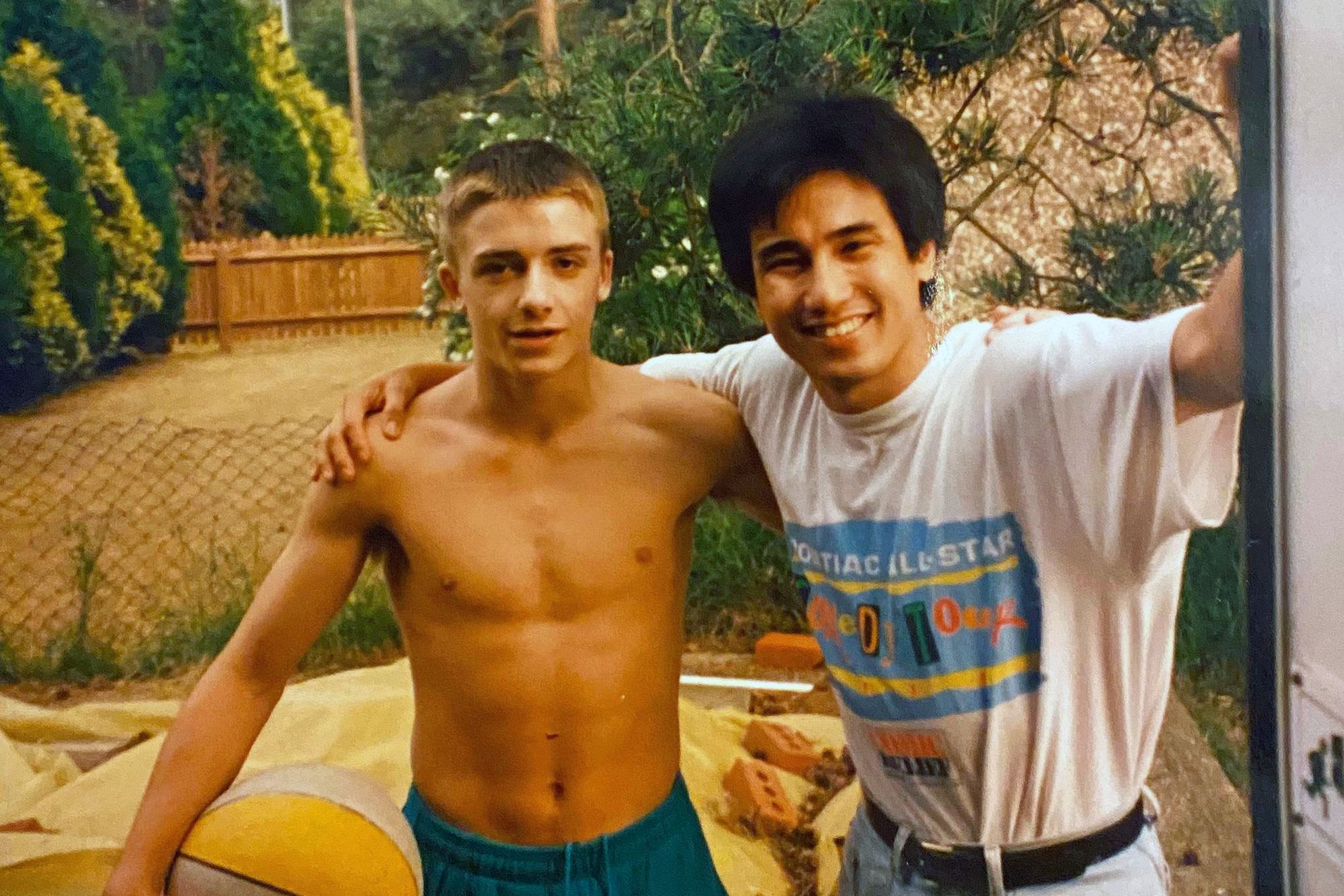

So, that summer I convinced my German roommate to go west to LA with me for the summer. My roommate thought it would be cool for him to explore Southern California for the summer while I did my judo. So, we packed up our stuff and drove out west. When we arrived, we checked out one of the biggest judo clubs there to see if they knew where I could find Nishioka. The folks there told me to try one of the clubs in the city where apparently Nishioka taught. But when we went there, he was nowhere to be found. I told the folks there I really wanted to do competition training and they told me to try LA Judo Training Center, which was run by a guy named John Ross, a former national coach.

I spoke to Coach Ross and explained to him that I had decided to spend the summer in LA to learn judo. I told him I didn't have much money and asked if he knew of any cheap accommodations near his club. He told me I could sleep in the dojo to save money. He would provide me with a sleeping bag and a pillow. To earn my keep, I would have to teach the children's class in the early afternoon, and in the late afternoon, his assistant coach would give me daily personalized training for two hours. And in the evening, there would be the regular class, taught by Coach Ross, which was also for two hours. So, for that whole summer, I'd spend four hours a day doing a mix of personalized training and group training.

Early in my stint there, an overly zealous brown belt asked me for some newaza randori. At that point, I had had no personal experience with armlocks. Of course, I knew what an armlock was but at my university club nobody did it. The brown belt guy rolled me into a juji-gatame position and yanked out my right arm. I heard a "crack' sound, felt a searing pain, and screamed out loud. He let go straight away but the damage was done.

I told Coach Ross, "I think my arm is broken". He took a quick look at it and said, "Don't worry about it. Just wrap it up and you'll be fine."

"But I really think it's broken," I said, adding that I had heard a distinct cracking sound when my arm got straightened. Coach Ross muttered something about how he once broke his shin bone during training in Taiwan and he just tied a wooden stick to use as a splint so he could continue training. "Don't worry about it," he said, again. So, I didn't. I wrapped up my arm tightly to provide some compression, and continued training like he told me to. (On a side note: Decades later when I had my arm X-rayed, the doctor said he noticed some bone fragments floating around my elbow area. "Did you ever break your arm?" he asked me).

My arm hurt for that whole summer but I had travelled over 1000 miles to learn judo in LA. There was no way I would give up just like that. Of course, I protected my arm during training and it helped that Coach Ross had asked me to learn to grip left-handed. That wasn't because of my injured arm though. He had showed me a video tape of the great Toshihiko Koga, who gripped left-handed and told me to emulate that style of gripping.

There were a few key things that I learned from Coach Ross:

a) The importance of gripping

b) The importance of newaza

c) The importance of tactical play

d) Ippon-Seoi-Nage and Yoko-Tomoe-Nage

When it came to gripping, Coach Ross told me: "If your opponent can't get a grip, he can't throw you, so never let him get a grip."

As for newaza, he told me that because I had started judo late, I'd better work on my newaza because I could make much quicker gains in newaza than tachi-waza (which would take much more time to develop).

Coach Ross told me about Aurelio Miguel, the 1988 Seoul Olympic Champion who won every single match through penalties. "This shows that you don't necessarily have to do a throw to win a match," he said. "This guy won an Olympic gold medal without scoring a single point."

For my tokui-waza, he suggested that I study Koga's Ippon-Seoi-Nage and gave me some video tapes of Koga which I watched over and over again. I actually learned to do that throw quite quickly. It came naturally to me. He also recommended Yoko-Tomoe-Nage. That one took forever for me to learn. It was literally years after I had left LA Judo before I could get Yoko-Tomoe to work.

During my three months at LA Judo, I had assiduously avoided that brown belt who had broken my arm. But on my last week at LA Judo I asked him for a newaza randori. Three months earlier, he had destroyed me on the mat. This time around, he had a much harder time. And before the randori was over, I managed to choke him to submission. He was stunned. And I was satisfied.

At the end of summer, Coach Ross awarded belt promotions to several members of the club. Almost all players got promoted. Several of the brown belts got their black belts. I had expected to get promoted to black belt too but he didn't promote me. I guess that was his way of telling me: "You've still got a long way to go, kid."

I learned a heck of a lot from Coach Ross, who gave me my foundation in judo and taught me to be tough and hardy. When I told him I was there to do serious competition training, he held me to it. He never took it easy on me, even though I was training with a fractured arm. I remember there was one day when my whole body felt so beat up, I told him I wanted to take just one day off, and he berated me for it. "I thought you were here to train!" he bellowed.

After that summer, I went back to my university judo club. That's when I realized my judo had been transformed. At LA Judo, I couldn't really see the progress because everybody was so much better than I was. But back in my university club, nobody could throw me anymore. And Brendan's foot-sweeps weren't working on me anymore either. I even threw him with ippon-seoi-nage, which thoroughly stunned him. He complained afterwards that I was grip-fighting too much. I didn't care. It was clear my judo had made quantum leaps because of my stint at LA Judo.

The very next summer, I decided to find Neil Adams, the famous World Champion and armlock specialist. I knew he had trained at the Budokwai, so I bought a ticket to London and found my way to that famous judo club. The manager there told me that Adams no longer trained there, and that if it was full-time competition training I was looking for, the Budokwai wasn’t the right place because it didn’t have a full-time training facility. He recommended that I go to Camberley Judo Club, which had a dormitory and full-time training.

He also introduced me to Nicolas Soames, a member of the Budokwai who was a famous judo journalist. He covered judo for several newspapers using his real name for one of them and pseudonyms for the rest, so that it wouldn't be obvious that the same person was covering judo for all the papers. One of the aliases he used for one of the papers was Tomy Nagy (yes, he liked Tomoe-Nage).

Nicolas also published judo books under an imprint called Ippon Books. Two of the books he had published were Armlocks by Neil Adams and Grips, also by Adams. I had almost all of his books and pointed out some factual mistakes he had made on a few of them. He asked me to show him and when I did, he was impressed. He asked me if I wanted to work on some book projects and I said I would be delighted to do so.

As for training, I was given some referrals to Camberley and took a train out there (it was about 50km away). The head coach was a guy named Mark Earle, who was a contemporary of Neil Adams. He was a competitor himself, with some international experience.

At the club were a bunch of boys and a few girls who were training full-time. The dorm was tiny, with eight guys sleeping in bunk beds in one big room. There was basically a bunk bed against each side of the four walls of the room. Normally you'd think it'd be rather difficult to fall asleep with seven other people in the room but we were always so tired at the end of each day that all of us would fall asleep the moment we hit the bed.

The guys noticed I had only two training gis with me. They said that won't do because firstly, I'd need far more judogis. Secondly, my judogis were way too thin. They showed me what a proper competition judogi looked like. It was new to me but I told them I couldn't afford to buy competition judogis right now. Several of them decided to donate some hand-me-downs. Basically, old judogis that they were willing to part with. Before I knew it, I had up to six or seven old competition gis.

Although I was the only non-British player there, the guys treated me as one of their own and I became integrated into the club very quickly. When the British team went for an international training camp, they took me with them and told the organizers I was with the British team, so I could get in. That was my first exposure to training with top Japanese, German and Russian players.

The training at Camberley was tough. The coach would wake us up at 6am and get us to go for a run. We'd come back, eat breakfast and rest. Around noon, we'd do strength and conditioning work. Then some lunch and rest. In the afternoon, we'd do some technical work. Then more rest and more food. Lastly, there was the evening session which would mainly be randori.

Camberley was a famous judo club and we had some top players from other clubs come to train with us, including two players who would go on to become World Champions. Nicola Fairbrother was a -56kg World Champion in 1993 and Kate Howey was a -66kg World Champion in 1997. I was one of the lightest players in the club at -60kg so I did quite a lot of randori with them.

On Tuesday nights, our coach would drive all of us in a van to London so we could train at the Budokwai. Their Tuesday randori was when top players from various club would come to train together. Those sessions were rough. There was one time one of my friends from the Budokwai got into a fist-fight with a player from Neil Adams’s judo club. I had to pull them apart. Later, after they had both cooled down, they had another randori with each other.

On Wednesday nights, we’d be driven to the High Wycombe Judo Club, which was a Centre of Excellence. Even more judokas would gather there for joint randori. Imagine a dojo with about 30 or 40 black belts on the mat. It was randori heaven.

I’d travel back to London on the weekends so I could train at the Budokwai. The experience there was very different from that of Camberley. The Budokwai was a very cosmopolitan club with players from various countries. It mainly catered to working adults and, in many ways, KL Judo is modeled after that.

Its members came from all walks of life. I remember there was an elderly chap, who worked in construction, who was an expert at a leg grab called Kibisu-Gaeshi, where he would reach down and grab the heel. He caught everyone with that at one time or another. I got caught with it several times before I wised up and figured out a way to stop him.

Mark Law was an editor at the Daily Telegraph, a newspaper, who decided to take up judo as a 50th birthday gift to himself. Mark was a white belt when I met him at the Budokwai. It wasn’t easy for him taking up judo at 50 but he had caught the judo bug and was determined to make it as a judoka. Mark would later write a critically acclaimed book called Falling Hard about his love affair with judo.

Years later, when I visited London, he heard I was in town and asked me to visit his home. We had some tea and a nice chat, talking about judo of course. We also had a randori at the Budokwai. By that time, Mark was already a black belt and not so easy to throw anymore.

Another famous member was Terence Donovan, the acclaimed photographer who did a beautiful book called Fighting Judo with Katsuhiko Kashiwazaki, a World Champion who taught at the Budokwai when he was in London to learn English. When someone pointed out Donovan to me, I approached him and told him I was a fan of his work. He replied, “You like Addicted To Love, do you?”

It so happened that I did like Addicted To Love by Robert Palmer but I wasn’t sure why he mentioned that until he explained that he had directed the famous video for the song. We proceeded to do randori. Donovan was big and black belt but I was young and nimble so, he couldn’t throw me.

Nicolas Soames, the famous judo journalist and publisher, introduced me to David Finch, a legendary judo photographer, who was also a member of the Budokwai. David would become my friend and collaborator for decades to come.

I didn't spend that entire summer in the UK. I had heard that Daniel Lascau, a Romanian refugee who had become a surprise World Champion in 1991, had trained at the Russelsheim Olympic Training Centre. Russelsheim was near to Frankfurt, where my college roommate’s mother stayed. So, I spent time in Frankfurt for a few weeks.

My roommate’s mother called up the head coach at Russelsheim, a man named Franz Fischer, who had represented Germany in the 1967 and 1971 World Championships. He was one of those European pioneers who had set out to Japan in the early 60s to learn judo. When I met him, he told me I could train at Russelsheim and also at his own judo club in Frankfurt.

When I was there, Lascau had already left Russelsheim for another club but Coach Fischer introduced me to Hans-Joerg Opp, a national player who had once fought the great Koga. It was Hans’s job to take care of me while I was in Germany. We clicked straight away. Hans would become my best friend in judo as well as my matside coach at the 1993 World Championships.

There was one time after training when Coach Fischer invited me to join him for a dinner that he was having with his friends. At dinner, we got into a conversation about judo and never stopped talking throughout the whole dinner. I was enthralled at his judo stories and it was only later that I realized I was kind of rude and inconsiderate to have taken all of his attention when he was supposed to be there to have dinner with his friends. He barely got a chance to talk to his friends. But he didn’t seem to mind.

My other coaches had taught me technical stuff and how to be tough. But Franz Fischer taught me about another aspect of judo that is often overlooked. He taught me about love and kindness. He also taught me to believe in myself.

Before I left Germany, he invited me to have a meal with his family. After the meal, when we were chatting in his front lawn, he told me, “Oon, you can be whatever you want to be. You can achieve whatever you set your heart out to achieve. It’s all up to you.”

I returned to the UK and trained for a few more weeks before I had to head back to the USA to resume my studies at the university. Before I left, Nicolas gave me two book projects to work on.

The first one was to be called Great Judo Championships of the World, which was a collection of judo results from various major international competitions. It also featured profiles of famous players. The pictures were all supplied by David Finch. That was David and my first collaboration.

Such a book wouldn’t make sense today in the age of the Internet but back then there was no such thing as online. So, it was an incredibly useful book especially for journalists. At the 1996 Atlanta Olympics where I served as judo information officer, I met a bunch of Japanese journalists who were assigned to cover the judo event. When they realized who I was, they each pulled out a copy of “Great Judo Championships of the World.”

The second project was a book on ashiwaza by American World Champion Mike Swain. For that one, David and I had to fly out to San Jose, California, to do the interview and photoshoot with Swain. We wrapped that up in three days. It would take more nearly half a year though to write the book and oversee the layout and design.

While in London, I also met the folks from Fighting Films, which produced these great videos featuring colour commentary by Neil Adams. I asked them why these videos were not available in the USA. They said it was too expensive to export them there. So, I worked out a deal with them to have the videos (VHS, mind you) reproduced in Texas, where I was studying and I would sell them through mail order and at judo competitions throughout the USA. I would pay them an agreed royalty per video reproduced. Nicolas had also given me a set of books to try to sell in the USA. He told me once those sold out, I could order more and he would ship them out to me. Selling Ippon Books and Fighting Film products while I was still in college was the start of my long-term relationship with these companies.

When I got back to the States, it became apparent to me how inadequate my judo training was at the university. I joined the wrestling club just so I could get more training. I would also encourage and cajole friends, roommates, classmates and anybody I could find to train judo with me.

When I went to the university dojo, which was open every day (even when there was no judo class), I would bring along an extra set of judogi. Whenever someone peered into the dojo, I would invite them to come in and ask them if they would like to try judo. I did judo with karate people, taekwondo people, aikido people. Just about anyone who was willing to give judo a try.

It wasn’t an optimal situation but it allowed me to train every day. It would have to do for the next nine months until I could go back to Camberley again the following summer.

End of Part I